Documenting the Unseen

On a journey in 2011 through southern US cities, Linh Dinh gathered images based on race and class distinctions. The photographs I’ve chosen to discuss represent public scenes in urban areas, and as you’ll see, the textures of experience vary. By stressing the importance of everyday urban street scenes, Dinh explores the limits of the power of visibility in environments of racial and economic disparity by focusing on public situations and appositional relations that reconfigure how performative and disciplinary actions can be revealed in often-inconspicuous locales. The non-iconographic image successfully elides the realm of art system and mediascape, inviting critical inquiry without the required aid of categorically motivated analyses. Dinh’s work can be seen in this way to confront the “visibility trap” of mainstream media by relocating visual perspectives in less visible urban contexts.

fig. 2

In part, Dinh justifies his ethnographic tactics based on a complicated relationship to imperialist history in his home country of Vietnam, where Western media constructed a visibly incomplete representation of US aggression, terror, and violence. While iconographic images like Nick Ut’s “Napalm Girl” and Eddie Adams’ “General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner in Saigon” represent the trauma of Cold War imperial conflict, they also serve complicated purposes of persuasion in the maintenance of a US nationalist imaginary. Dinh therefore is motivated to turn his camera onto his adopted country to participate in a documentation of overlooked and economically-stressed American neighborhoods that are often left unacknowledged by contemporary media. To this end, Dinh spends time in city spaces and neighborhoods interacting with people and objects in contemporary settings that are often subject to dire economic and racial inequities. More in the tradition of the documentary photography movement instigated by Roy Strkyer, head of the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression, Dinh’s photography references an older generation of visual artists. Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, John Vachon, Russell Lee, and other Depression-era documentary photographers who addressed the plight of laborers in economically stressed areas of the US heartland in the 1930s created an archive that informs Dinh’s verité approach to photography. His images convey a sense of immediacy and realism that contrast starkly with the more visible public representations of race in popular media formats. Spontaneously organized, Dinh’s work reveals some of the visual textures of public life he encounters.

In figure 2, for instance, four people walk in an ordinary urban setting in Charlotte, North Carolina. The graphic text on the man’s shirt draws attention in terms of its centrality within the frame of the picture. “Cash rules everything around America,” as a slogan of capitalist reality, or as an acknowledgment of material access, floats ambiguously through the frame. It also shows appreciation or identification with the popular New York hip hop group, Wu-Tang Clan, whose 1993 song, “Cash Rules Everything Around Me,” forms the acrostic, “CREAM,” written on the man’s shirt. A resigned and complicated reflection on violence occurs throughout the song, and is seen in the alternatively forceful and sexual pun: “CREAM” as verb is overlaid onto “CREAM” the noun. The large ring on the woman’s hand, while coordinating color schemes with her purple shirt, also correlates with the textual message. Cash rewards social relationships, provides material goods, and solidifies power relations. Magnified bling, however inauthentic as precious gemstone, suggests an affinity for the imagined status, power, and privilege money brings, particularly in relation to whiteness and a promotion of white values in terms of power and commercial access. If we try to answer the question why “cash rules,” both as it appears on the man’s shirt and as it is used as a refrain in the song, we might come to a number of conclusions: “Cash rules everything around America” because it gives us purchasing power and status over others. Cash rules because it’s our only medium of survival in an era of economic coercion based on the largely unregulated requirements of global finance. Cash rules because unlike plastic debit or credit, it’s immediately legible in any situation. Cash rules because it can mediate sexual power and relationships. In this visual context, the slogan bears force in relation to the visibility of economic identification representationally coerced in the form of bodies as images. The contrasting economic violence and racial segregation that underwrite my reading is animated by impositions of prosperity in the social order of things. The visible subjects of the frame are understood in relation to racial and economic narratives that align black lives within the catastrophic impositions of what is commonly referred to as the American dream. Such a “dream” and its culturally inscribed codes of success in part mark my reading through racial political ontologies.

The binary perspective of the visible/invisible also can be revised rhetorically to focus on the performative context of the situation. The photograph does not represent an iconographic moment of national significance. Quite the opposite is at stake: the image shows a group of people on a walk in an ordinary urban environment. The displays of class and race in bodies as images are consciously represented by clothing and hairstyles: the people in the photo seem to associate with visible cultural cues that reinforce types of identities in which they participate. The associative imagery, seen most prominently in the Wu-Tang Clan shirt, forms part of a larger collective commitment to sartorial gesture, or codes of representation that Dinh captures, not for public consumption, but for creating a query into the limitations imposed by the boundary between the visible and the unstable signs of public marking. Although Dinh’s images are posted to his blog, Postcards from the End of America, and are less available to public consumption, they form a stable and accessible archive, frequently updated, and mediated by textual comments. Dinh’s relatively small, but devoted, viewership therefore can see the people in figure 1 participating in a familiar exchange of the everyday. The representation of social relationships, and invisible political ontologies that accompany visual representation, determine how Dinh’s viewers might read into the image.

There is another group of people featured in figure 2. A graphic image dominates the frame of the picture in the form of a red, white, and blue gun, the color red ominously seeming to drip blood (here again, the acrostic, CREAM, appears just under the image). The gun, as both fashion object and personal announcement, intrudes on the public occasion of domestic unity to indicate a tension in expressed values. Read in sequence with the “Cash rules” frame in figure 1, we get a sense of contemporary public narratives interwoven with a violent chain of signification. The often-tense stakes of economy and survival are mixed in these images with humanistic values of communal relation and respect. The people in both frames are observed in private moments of urban ambulation. The public surface they compose, however, reveals conflicting possibilities in the tensions of ideological texts and images of power, submission, and control. The oversized rings in both images, along with the dreadlocked and goateed youth, display marks of racial legibility in fairly innocuous urban environments (there are clean sidewalks, brick buildings, some foliage to situate the more dominant presences of bodies, jewelry, and other fashion choices). Both pictures represent narratives of peaceful coexistence even as the main graphic markers counter those claims. The textual and symbolic intrusions, as indicated by both men’s shirts, and by the women’s jewelry, suggest a reality that prepares our reading of the urban experiences of these individuals. Dinh orients attention to key images within the photographic frame, and asks us to better understand conflicts of interest that separate our everyday modes of public discourse.

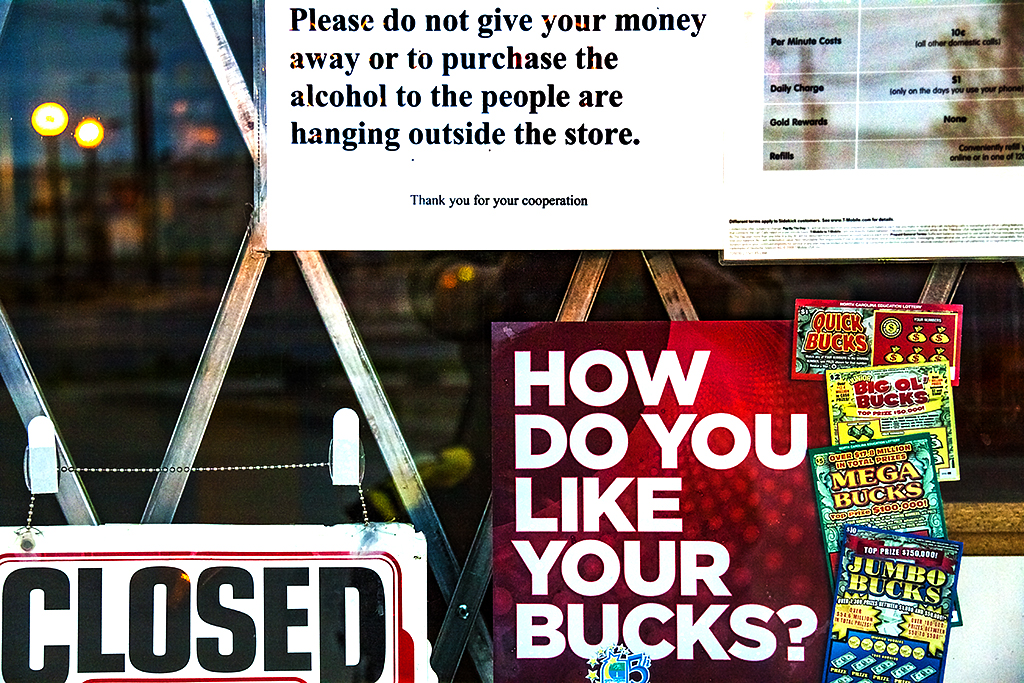

fig. 3

The organization of photographic events lets us see into public moments that might otherwise pass by as uneventful or routine civic exchanges of daily urban life. By deliberately seeking circumstances such as these, declaring significance within the everyday forms of mundane experience, Dinh argues for new ways of looking into the dynamic and insoluble animations of public life. The images retain public tensions we may all recognize (guns, displays of wealth, creative personal identifications), but they also reveal incongruent positions, tense domestic and public relations, and undisclosed claims of social, political, and economic potential. Viewers are asked to acknowledge a representation of situated signs, codes, and performances that resist an easy visual legibility. As citations of performative moments, we also experience more than a system of significations. By looking at the situated concerns of the photograph, we can read the acrostic text on the man’s shirt in figure 1 in a way that echoes the image of the gun in figure 2: both associate masculinist identities in urban environments with popular expressions of power. The sartorial gestures sustain personal force through stylized actions that produce strength and create distance between an individual and hostile capitalist modes of domination. The image of the gun both attracts associations to the Wu-Tang Clan, but also produces a symbol of violent address that might suggest to viewers uninitiated in the narratives of hip hop culture to beware. While the slogan “Cash Rules America” relates to a violent self-exposure within the codified promises of the American Dream, it also could be seen as a talismanic figure of empowerment reinforced by the popular success of hip hop musicians. By wearing these shirts both men reveal identifications with popular culture that may get them a little further along.

fig. 4

Homeless Margins

In Charlotte, North Carolina, Dinh approaches our sympathies indirectly, finding displays of race and economic disparity in the forms of lottery tickets and a written merchant’s request to refrain from making financial donations to panhandlers (figure 3). A conflict is startlingly obvious: gamble on state sanctioned games but don’t increase the chances for others who are too impoverished to participate. As in the previous photos, cash is king, but the “Jumbo Bucks,” “Mega Bucks,” “Big Ol’ Bucks,” and “Quick Bucks” are sanctioned opportunities for certain types of citizens who can afford them. The fuzzy grammatical structure of the proprietor’s sign also narrows the distance between the possibly foreign merchant and local vagrant. The intersection of poverty and lottery coheres in a public moment framed by a visual organization of the lens that manages to put into conversation several distinct textual displays. Such coordinates of public meaning in the photograph ultimately lead to private alienation from the larger common weal. As a witness, and agent, of the signs of private (mis)fortune, Dinh puts in motion antithetical public (and mercantile) codes that invite us indirectly to acknowledge the social alienation of others.

fig. 5

Figure 5, also in the Charlotte series, makes a similar claim. Taking up much of the lower right portion of the photo is a sign showing the image of an outstretched hand next to the following message: “On the street, real change doesn’t come from your pocket.” While the image of the hand reaching for handouts is difficult to interpret based on corporeal or phenomenological determinations of race, it is impossible not to consider the political ontologies at stake in this representation. Additionally, the pun on “change” rhymes with Obama’s 2008 campaign for change (and is topic of another photograph seen in figure 6 below). Elements of the textual display read as follow: “Homes end homelessness, handouts enable it. Please say ‘no’ when asked for cash on the street.” The deceptive incongruity of the argument is heightened by the background signage announcing Ruth’s Chris Steak House. An African-American man and an Asian woman occupy the far left portion of the image, the only human figures in this oddly distorted public display of corporate, municipal, and philanthropic claims. The smaller print on the sign addresses alert passersby as well: “To make a REAL CHANGE, invest in agencies providing services to the homeless.” A URL leads to information in the Charlotte area about organizations and services that provide aid for homelessness. Groups like the Salvation Army and the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Coalition for Housing are prominently featured as appropriate sites for public donations. While this isn’t the space in which to debate the aims of programs or services designed to “end homelessness,” the antithetical claims give pause. Urban civil society in the photo is striated with corporate, municipal, and philanthropic statements that reinforce tropes of racial embodiment without acknowledging the specialized features of social and economic suffering that underwrite many of the problems of homelessness. The personal claims by way of fashion codes and bodily affect (notice the bright blue sneakers and smiling face of the woman) contribute also to how we see the image. There’s a problem (homelessness); the evidence for the problem is organized in the textual design of the signage. Against this the happy couple and the corporately owned steak house exist as reminders of another, more abundant, version of public accord.

fig. 6

The dialectical tension between mixed-race bodies and images of abundance again is situated in signifying chains of argument that institute America as land of opportunity. The propagandistic logic encapsulated in this photo assumes many Americans share in the proposal of opportunity as a defining feature of the nation, just as the promise of multicultural diversity is evenly extended in the current economic landscape. Of course, not all Americans find that opportunity, and many are homeless. Homes, not a reorganization of public welfare, capitalist ideology, or political realization, are offered as the vehicle of change. In other words, change is important, but only the right kind of change counts. By seeking such images, Dinh is using the medium of photography and the grammar of photo documentarians (street photography) for activist means. This work, as mediated by his blog, reveals his concerns as a visual activist committed to a stance similar to one announced in 1970 by Amiri Baraka: “There is no such thing as art and politics, there is only life and its registrations” (“Black Nationalism” 11).

The photograph of a homeless man in figure 6 pushing a shopping cart in front of Old Navy in San Francisco competes with the Charlotte Homes-instead-of-Homelessness image. The Old Navy corporate logo appears in the top right corner. A man plugged into what looks like an iPod happens by, occupied by his device. A woman appears, eyes down, avoiding the homeless man. The glimpse into city space also reveals wide streets, an area designed for car culture, not, perhaps, for foot traffic, let alone shopping carts. The ironic presentation of the over-piled shopping cart next to the smaller (due to perspective) representation of passing cars brings attention to homelessness, and to the predominant narratives of purchase or scavenging (notice the many bags the man carries). The image also provokes concerns regarding home, security, comfort, and transportation in contemporary cityscapes. In many ways, the photographic features align problems of urban ideology, class limitations, and structural realities of contemporary cities. The frame amplifies these themes by asking viewers to look more intently at a moment of public composition that might otherwise pass unawares. Certainly, those of us in large cities witness such scenes on a daily basis. By framing and organizing what might otherwise pass as barely noticed, Dinh asks us to enter indirectly the buried and often conflicting values and beliefs that burden public life in modern cities. While Phelan might argue that the project of making the homeless man visible actually reduces him to a body-as-image, removed from the humane context of his life, for Dinh, the “trap of visibility” requires judgments that renew strategies of seeing. The topic, in other words, is not the homeless man, but the ethics of urban scenes of representation, and the performances that produce potential acknowledgment of the economic conditions in the contemporary US, all bound by political ontologies of race. While his features do not concretely establish easily recognizable biological or phenomenological racial characteristics, it is difficult not to read a subtext of race as a system of hierarchies in national, social, and urban spaces in this image.

In figure 7, we see a claustrophobic intensity of populist political and religious imagery. Obama, with the caption of “Change we can believe in” next to his confident profile, is contrasted starkly with the wistfully smiling angel figurine. The image (is it televised? digital? graphic?) is shown next to the ghostly reflections of the glass window storefront separating the angel from Dinh’s camera. In context with the other photographs, Dinh’s presentation of national ideology along with a religious symbol of belief suggests a kind of hopefulness in American public life that is posited in unrealistic terms. The dangerous thread of magical belief in change (from above or beyond?) derails the materialist conditions of capital, market realities, and political collusions that make life increasingly difficult financially for many in today’s overpriced and underemployed city centers. Faith, whether in ending homelessness by putting people in homes, in representations of the violence of discourse that rewards racial aggression, or in images of an African-American president pledging change, contrasts sharply with democratic values of argumentation, deliberation, and rational organization in the course of ordinary life. By joining diverse registers of American experience, Dinh makes visible what often passes us unseen. By acknowledging the distressed conditions of contemporary city spaces, he asks viewers in turn to acknowledge their own indirect participation in the unbalanced systems of economy that can determine courses of action in contemporary society.

fig. 7

From a Sketch Book: Walking South Philly

This is how Linh Dinh works: he walks through urban areas in Philadelphia and in other cities he visits, taking pictures of people, objects, and environments that catch his eye. Physically, Dinh somehow blends into his environments with seemingly minimal effort. He sometimes asks permission to take photos, or he offers exchanges of cigarettes or beer for the images, particularly of the homeless, when he visits heavily-trafficked urban streets. There are textual records of conversations with his photographic subjects on his blog, and Dinh’s down-to-earth conversational appeal quickly negotiates the social cultural interfaces between himself and others. Often, his photographic subjects are not aware that he is observing them. Sometimes it is dangerous to work in this way. Once in 2008 I accompanied Dinh to the downtown devastation of Camden, New Jersey, where the tense economic despair and the moods of passersby required that he keep his camera hidden: not unexpectedly, he did not take any images that day.

In May 2012, I met Dinh in South Philly’s Italian Market. He wanted to introduce me to the many diverse aspects of his adopted neighborhood, and we visited meat stalls and live animal markets before venturing further out into the outskirts of Cambodian and Irish neighborhoods. We began our tour at Geno’s Steaks near the intersection of 9th Street and Passyunk Avenue (just across from Geno’s rival, Pat’s King of Steaks, the oldest cheesesteak restaurant in Philly). Joey Vento, proprietor, passed away in 2011, but his presence, for good or bad, established a strong public following (many disliked the notorious “English Only” rule for ordering food at his establishment). Vento had a strong sense of how to generate publicity, and many in the area (and far beyond) are loyal customers. The gaudy and colorful storefront resembles a kind of Las Vegas casino on a much lower scale. The day I was there, crowds had gathered in the heat to order sandwiches and drinks. Walls along the storefront next to the pick-up window were covered with images of Philadelphia law enforcement officers and other mementos celebrating the police force. A shrine to Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner, victim of a controversial 1981 murder that ended in the conviction of Mumia Abu-Jamal for the crime, was featured prominently. In a storefront cattycorner to the restaurant Vento’s Harleys and other memorabilia were presented in a glass display window. Dinh also pointed out a large mural of the iconoclastic Philadelphia mayor and politician, Frank Rizzo, while recounting stories of his conservative presence in the city, and how people in South Philly had loved him. The neighborhood revealed a complex weaving of competing racial signifiers that came to life in civic features such as: newly created community gardens; historic public sites of transaction like Geno’s; community murals celebrating the multiracial characteristics of the city; civic design founded on narrow streets that shaped tightly-knit communities. The public realities here were supported with historical representations, markers of civic pride, and strategies to revamp certain areas for real estate gentrification. The Italian Market itself is a complex community owned largely by Italians but managed by a new influx of Latino, Asian, and Southeast Asian merchants who pay rents to Italian landlords. But even these ethnic relationships are changing as the Italians more and more sell off their portions of the neighborhood, moving out toward suburban areas of the city. As an example of a public space in the contemporary US, it’s difficult to imagine a more complex, but highly efficient, urban exchange of racial realities in the ongoing imaginaries of civic life.

As we walked I observed how the row houses, built largely to house workers early in the last century, were mostly surrounded by concrete: the mazes of streets, sidewalks, plazas, and intersections were unrelieved by any shade this warm day in late May. Very few trees could be seen anywhere (schools also were difficult to spot, and when we did see them, they resembled large, brick prisons). One moment we found ourselves in a newly gentrified zone not far from Geno’s, the next we had turned down a beat-up neighborhood street marked by broken taverns, graffiti tags, and uncollected trash. In one Cambodian neighborhood we stepped unexpectedly into a makeshift street festival. A center “stage” revealed children in bright costumes performing traditional dances as the crowd barbecued chicken, or swilled Heinekens from coolers kept near them under tarps to keep away the sun. Old folks sat in lawn chairs fanning themselves while children rode astride the shoulders of their parents. After a while we stepped away, and as we walked, we noticed children playing in inflatable pools on the concrete sidewalks in front of their homes. The street life was vivid, practical, and alert to the pleasures of a warm afternoon.

fig. 8

The density of neighborhoods and racial divisions are intense in South Philly. Skirting an industrial zone near a government housing project on 25th Street, a road that separates (not joins) the neighborhoods of Point Breeze, historically populated by African Americans, and Grays Ferry, traditionally occupied by Irish Catholics, Dinh noticed how several freeway overpass support beams had been optimistically painted red, white, and blue (figure 8). In a caption under the photo on his blog, he writes:

After a mile or so of crumbling concrete and exposed, rusting steel rods, a few painted columns, then another mile of naked decay. In the back is a brightly painted charter school. This is the road dividing Grays Ferry and Point Breeze. Point Breeze sounds idyllic, but it's one of the deadliest neighborhoods in Philadelphia.

The decayed infrastructure contrasts sharply with the sudden emergence of painted columns in this racially divided area. There is something unreasonable about the painted beams being where they are, but they also stand out as an attempt to symbolically unify the racially compact and contested neighborhoods. The columns delineate a particular boundary between places, a makeshift marker of national identity amidst the forlorn reality of a city often at war with itself.

fig. 9

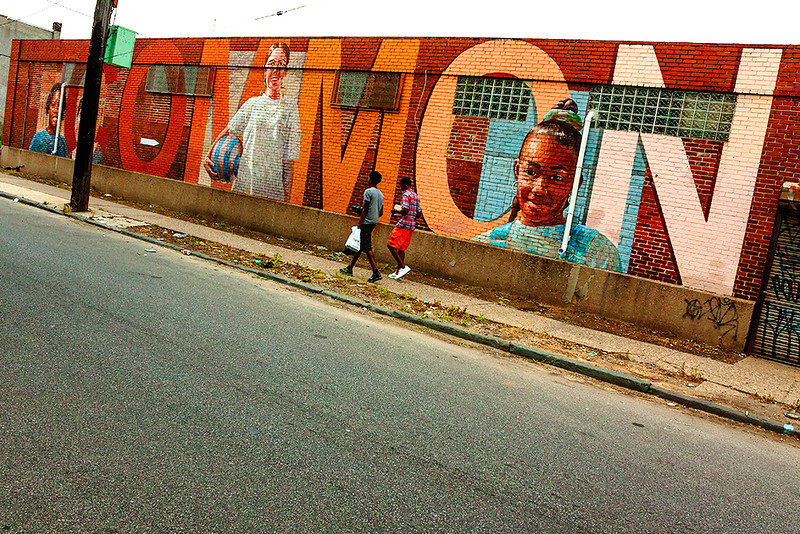

A little while later, by the “painted charter school” Dinh described above, a peculiar and unexpected thing happened. As Dinh took pictures of the school mural (figures 8 and 9) a young white woman slowed her car next to us, pointed to an area of the painted features on the building, and identified herself as one of the youth in the mural (you can see her in figure 10 between the two letters M). Suddenly, and unexpectedly, the mural had come to life in the distance between the painted figure and the living model. No longer a schoolgirl, the passing of time was present in the woman’s features. As she talked we witnessed a great sense of pride in her descriptions of her time at the school, and she remembered when the mural was being painted and how several of the students from the racially mixed school were used as models.

fig. 10

The woman still lived in the Grays Ferry neighborhood and showed a sense of pride and appreciation for our interest in this particular charter school mural. Dinh asked if he could take her photo. She consented, with a mixture of accomplishment and humility, and he took her picture there as she sat looking at us from her car (figure 11). Dinh shared the digital images he had shot, thanked her, and she drove away. We were both impressed by the synchronicity of the occasion. The woman’s civic pride suggests a range of emotional relationships to the public culture she participates in. Seen through a mode of citizenship, this event displays the significance of belief and desire in the formation of public attitudes around racial representation insofar as the mural indicated an optimistic profession of values situated in the context of racial integration.

fig. 11

Despite the mural’s depiction of a naïve multicultural diversity in the images of multiracial children, I had originally felt hopeful about the encounter with the woman, and in a previous draft of this essay, I had included this anecdote as a moment of optimism. The young woman still lived in a diverse area of the city. She was proud of her neighborhood and of its institutions—a very positive thing, indeed. But there were disturbing cracks, like fault lines, running everywhere—through the neighborhood, the city, the nation. Cracks divided the woman, divided me. Certainly, it is inappropriate, or just plain wrong, to conclude with such a whitewashed reality, however sympathetic I may be to the figures, real and imagined, painted in the mural. Indeed, it is against those sympathies in myself I am here determined not to write. The description of the structural violence of racism in the Trayvon Martin trial cannot be seen apart from civic scenes of daily life. When our optimism intervenes to confirm institutional racial hierarchies, promoted through the good will of civic administrators, teachers, public artists, journalists, and others, something still escapes. Speaking of this sense of fugitivity with great animating power, Fred Moten says:

Perhaps the thing, the black, is tantamount to another, fugitive, sublimity altogether. Some/thing escapes in or through the object’s vestibule; the object vibrates against its frame like a resonator, and troubled air gets out. The air of the thing that escapes enframing is what I’m interested in—an often unattended movement that accompanies largely unthought positions and appositions. (182)

Here Moten addresses “the black,” objectified as a kind of body as image, and he draws our attention to the distinction of racial ontology as separate from the physical or phenomenological body. It is in that ontological field that race comes into being to give shape and determination to exchanges of the every day. Dinh’s images participate in this objectification, too, but in presenting the figures in urban settings, we encounter “the air of the thing.” What we can’t see, the reality of race, animates what we can apprehend, even determining how we see, based on the peculiarity of our perspectives.

Acknowledging Racial Realities

At a recent talk in Oakland, California, Frank Wilderson said, “the Left is convoluted and ambivalent above all about blackness.” He accused the Left of misguidance in its political thinking and actions due, largely, I think, to a desire to find solutions to problems, to extend coalitions that draw blackness into a frame that includes many other social realities, from homelessness to immigration. Importantly, he urged his audience to see how “blackness cannot be liberated or made legible for civil society.” His position is clear: “I’m not interested in doing coalition work,” he said. “I’m interested in theoretical work that helps black people shit on the inspiration of the entire world.” His advice to liberal whites was this: “Help keep the political context you’re in [free of] a need to find the common dynamic in everyone’s suffering.”

I bring up Wilderson’s remarks by way of conclusion because Linh Dinh’s non-iconographic photography actively produces images of urban life from a very similar strategic position. The goal for Dinh is not to document the hardships and hurts of individuals diagnosed in relation to conditions of social or political power. The political context of Dinh’s imagery focuses instead on how attitudes toward urban environments are located in specific moments of daily encounter and contribute to a theater of appearance in civil society. Social gestures, sartorial codes, and personal actions are not often seen as forms of life crucial to the acknowledgment of race in the larger frame of public culture. What we frequently address instead are publicly circulated racial representations that satisfy commonplace reinforcements of political ontology. An example of this can be seen in the racial slurs and verbal violence directed at tennis superstar Serena Williams. While the racist and sexist epithets focused on her are tweeted in the context of high-profile championship victories, the permission taken by racists who publicly attack her is generated in large measure through daily intimate actions that support and foster their disgusting attitudes. Therefore, it’s not surprising that controversies about race often erupt through circulations of mediated images in public contexts, where they are most visible. The photographic images circulated by today’s broadcast and social media, as seen in the George Zimmerman murder trial or in violent actions aimed at Williams, take part in a much larger structural violence directed at blacks in North America. By turning to the more intimate, daily exchanges of civil society, we can begin to see how everyday realities of race are framed and disseminated through life practices that are confirmed often according to one’s position in the ontological realities of race.

Non-iconographic documentation does not give us real bodies and “true” identities, but work such as Dinh’s acknowledges performative actions within situated contexts, and gives room to explore and understand how attitudes and actions based on race are shaped in urban environments. While, as Phelan recognizes, “[t]he challenge raised by the ontological claims of performance for writing is to re-mark again the performative possibilities of writing itself,” the act of writing does not lead to disappearance, but to acknowledging subjectivity’s participation in the construction of racial realities (148). The reduplication through the camera lens of civic performances in urban settings makes visible heretofore-unseen aspects of race and economic disparity in US contemporary culture. More importantly, Dinh’s work invites us to reflect on the kinds of responses we can bring forward to compete with the more prevalent verbal actions released through mainstream media. We can see how situated performances reveal subjectivities in motion, ones that constantly re-orient recognition. And as performance and its documentation inaugurate new subjective experiences, we can begin to ready ourselves for a future open to new foundations of racial acknowledgment, rather than enduring representations of unsettled grudges, such as those rehearsed during the George Zimmerman trial. Dinh’s aesthetic activism challenges us to acknowledge our responsibility as public participants whose judgments and actions contribute to how we see others in the larger context of institutional media, and in the facts of the everyday.

Dale Smith

.

2 comments:

Interesting perspective and analysis.

-j

i've had a hard time getting through this, as about half of it or more is 'academic' writing, postpostpostmodern america-style, where words are just big long things to insert like white cocks into black vaginas.

joking aside, there is some good here, especially in the description of how linh works and their foray into south philly's depths and also camden.

one striking thing: the quote by a frank wilderson (i believe) stating, if i remember correctly, that he wasn't at all interested in coalition building but wanted only to empower blacks to 'shit on the inspiration of the entire world'. what strange shit! (i do mean shit) this kind of academic, this great mind of the new generation, leads directly to the psuedo everything (but the hate seems to be very real) of that rapper mentioned above, banks her last name with rapunsel in her song title, or of richard prior's good friend the comedian paul mooney who i watched several months back spewing racial hatred.

Post a Comment