As published at CounterCurrents, Unz Review and Intrepid Report, 6/6/16:

In Japan, even a serious writer may be seen on mass advertising, and a translator can become a star. One of Japan’s most famous intellectuals, Motoyuki Shibata is a specialist on American literature. He has translated books by Thomas Pynchon, Paul Auster, Steven Millhauser and Stuart Dybek, among others. Shibata is also the editor of two popular literary journals, the Japanese-language Monkey and the English-language Monkey Business. His book of essays, The American Narcissus, won the Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities in 2005. Among the pieces are “Wonder If I’m Dead,” “The Half-Baked Scholar” and “Cambridge Circus.”

I got to know Shibata when he translated my short story collection, Blood and Soap, but we didn't meet until the Singapore Writers Festival in 2015. After an event in which we appeared together, Shibata pointed out that our Singaporean host was visibly more excited when introducing the American participants, meaning myself and Ravi Shankar. (No, not the dude who turned on the Beatles, but a poet and editor who was teaching in Hong Kong.) English is a formidable weapon, and our blue passports gave us extra cachet, even if neither I nor Shankar is native-born or whitish.

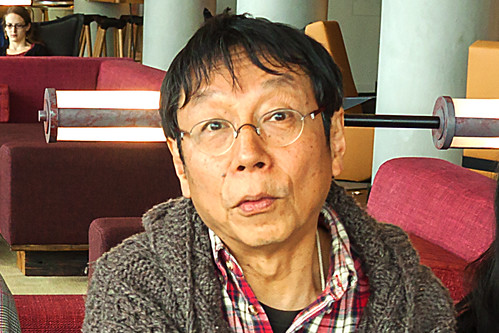

That evening, I had a few beers with Shibata and his wife as we sat under a bar awning that was pounded by bullets of rain. Unassuming in appearance, Shibata is also entirely free of conceits in conversations. This April, I saw Shibata in New York over several days, and again, he made some pointed observations about the U.S. and Japan. Why don’t we do a more in-depth interview? I suggested, and Shibata immediately agreed. Here, then, is the result.

How do Japanese view the United States, as far as culture, political system, politicians and foreign policies, etc.?

-“The US is no longer a model” would be the briefest answer.

During World War II, Americans were mortal enemies, but with the end of the war, America was suddenly a model, an ideal we should live up to, more so than the West in general was at the time Japan opened up in 1868 after 250 years of seclusion. Although there was always a protest against American militarism--“Yankee, go home!” was the first English sentence I learned as a kid--but there were plenty of things that made up for it: democracy (at least the struggle for it), equality (at least the struggle for it), jazz, movies, literature, etc. Even at the height of the Vietnam War, we knew that so many Americans were against it.

Things began to change perhaps in the 1980s. America began to look back, as if everything were perfect back in the 50s; the Reagan administration looked out for the rich rather than for the poor. And suddenly there were no more redeeming quality in America that used to compensate for whatever was wrong. America entirely ceased to be a model after all the havoc George Bush II made after 9/11. I gave a talk at a high school several years ago, and when I asked the students if they liked America, everyone said no. Then I realized that these kids belonged to the generation that grew up only knowing the Bush administration.

Some people have been disappointed by Obama, but I think more people--including me--sympathize with him and would like to believe that he would have accomplished more if the Republicans had not hindered him on every chance they got.

Did the high school kids say anything specific about why they disliked the US?

-When I asked them what they didn’t like about the US, they said: “Americans think they are always right”; “They force their ideas on others”. Remember, they only knew Bush’s America!

What were your own perceptions of the U.S. before you came here for the first time?

-First I learned about America from the TV dramas I watched as a kid. Father Knows Best, The Donna Reed Show, and I Love Lucy: a world of opulence where every family owns a big house, a family car, a refrigerator, and a vacuum cleaner, largely mythical commodities in Japan back then. It was an entirely different world which had nothing to do with me. Then I started listening to American and British music, and it seemed as if something new was happening every month in the late 60s: the Flower Children, Monterey, Woodstock... and though I was thrilled with all the new music it still was a distant world for me.

Please talk a bit about your experiences of the United States, and how your understanding of it has evolved over time.

-My brother went to live in the US in the mid-1970s, when he was in his early 20s. I went to see him first in Oregon in the early 1980s; he was living in a community where people came to stay over the weekend to enjoy hot springs and healthy food. I think I saw the best aspect of the United States then: a place where people are free to create their own community, free from profit-first mentality.

Then I lived in New Haven as a graduate student in 1984-85. It was hard for me to catch up with my studies but it was certainly not America’s fault! These twenty years I have been visiting the US once a year on the average, to see the authors I translate and more recently to launch my journal. Whatever problems there are in the US, I still feel this country is based on the idea of equality more than my own (though how much that idea is realized is open to questions, of course).

You go into a shop and the salesperson says hi to you, and you say hi back. In Japan, it’s not that way: the salesperson says Irasshaimase (Welcome to our store) and more often than not you don’t say anything back, you don’t even look at them: that’s the norm. A small thing, but it sort of epitomizes the basic premise on which human interactions are conducted in the two countries: horizontal in one, vertical in the other. Of course the ideal is betrayed so often in one country, and some equality is achieved despite the unequal assumption in the other, but the fact remains that the American premise is better than the Japanese.

These behavioral observations are fascinating to me, since they reveal so much about cultural differences and attitudes. Please give us a few more!

-In the “English” Ho Muoi invents in your great short story “‘!’” there are “so many personal pronouns, each one denoting an exact relationship between speaker and subject, that even the most brilliant student cannot master them all” (Blood and Soap, p. 16)--the Japanese language is exactly like that! You have constantly to remind yourself whether you are speaking to elders or youngers, to superiors, peers or inferiors--depending on that you refer to them as well as to yourself in different ways.

What attracted you to American literature in the first place? What makes it so distinctive?

-The idea that the self is--or should be--something you create, rather than something that is given to you, attracted and frightened me.

But the most important fact is that I had a wonderful professor of American literature when I was a sophomore. I wanted to be like him. If I had met a wonderful professor of British literature, I might be talking about Dickens and Hardy now, and my idea about the self might be more conservative.

Who would you consider the most representative American writer, and why?

-Herman Melville, because both he and his characters aim for the impossible and fail monumentally, which I think is very American. Mark Twain, because he established that American literature is all about getting rid of the literary from literature.

Recently in New York, we talked about the decline of both the US and Japan. How are these countries in trouble, in your mind? What lessons can the world learn about the problems afflicting Japan?

-I grew up with the assumption that politicians’ first duty was to make sure that not all the money went to a handful of people, that everyone got help whenever they needed it. No one seems to work on that assumption anymore, either in the US or in Japan. The lesson the world can learn from Japan? Don’t imitate America! Japan is imitating America in the worst possible way!

Japan has a highly intelligent and disciplined population living in a comparatively cohesive culture, and yet there is so much unhappiness, as revealed by survey after survey. The happiest adult Japanese are the oldest, those closest to death. It’s as if a weight has been lifted. Why do you think Japanese consider themselves so miserable, and what can be done about this?

-We work too much. You see, things really run right in Japan--the train arrives on time (they profusely apologize if it doesn’t) and the packages are delivered between 2 and 4pm if you so request--this is made possible because we work hard, not at the human pace but at the pace of computers. Working 9 to 5 is just a fairy tale to many office workers, and so many work from morning till midnight. Economy is bad on the other hand and jobs are scarce, so once you’ve got one you have to show your loyalty to hang on to it--therefore you work as hard as the next guy. What can be done? I don’t know if it can be done, but it would be really great if we became less ashamed about being lazy.

Resource depletion will be an increasingly grave problem for all countries, but Japan is particularly vulnerable. James Howard Kunstler has even declared that Japan would lead the global descent from modernity. In a Business Insider article, he states, “Japan's only good choice is to go medieval, that is, to give up on the rather hopeless 150-year-long project of being an industrial-technocratic modern super-state, and go back to being an island of a beautiful artistic hand-made culture.” Does this kind of thinking have currency in Japan?

-I’m not sure if medieval is the right word--especially if it involves returning to the former social structure with a lot of discrimination in it--but yes, after the 2011 earthquake/tsunami and the ongoing nuclear disaster in Fukushima more of us have grown suspicious about the equation of more technology with more happiness. One of the artists who have been living out this sort of thinking is Kyohei Sakaguchi, known, for example, for his Zero-Yen House Project.

The zero-yen houses are both tragic and hopeful, fascinating and appalling. If Sakaguchi ever comes to Philadelphia, I can show him quite a collection of zero-dollar dwellings!

.

8 comments:

Pondering “the possibility of Japan becoming the first post-capitalist society,” Morris Berman writes in a recent blog post:

It is perhaps the most schizophrenic of nations, having gone hog wild, since the postwar American occupation, for consumer goods and the hi-tech life, while having had the historical experience of the Tokugawa Era, roughly 1600 to 1850, of a tradition of austerity and eco-sustainability. As one Japan-watcher notes, the nation “is the leading-edge of the crumbling model of advanced neoliberal capitalism”; and yet, for 250 years prior to the hectic growth initiated by the Meiji Restoration in 1868, it got by with very limited economic expansion, and did extremely well. It cultivated organic farming, forestry management, commercial fishing, cottage industries, and a vigorous culture of recycling. Townsend Harris, who was the first US Consul General to Japan (1856-61), wrote in his diary that what he saw all around him was real happiness: “It is more like the golden age of simplicity and honesty than I have seen in any other country.” This was a society of urban gardens, community interaction, cheap public baths, itinerant repairmen, and craft work of very high quality, all proof that a steady-state economy can generate a vibrant culture. Beauty and luxury were found in simplicity and elegant design, rather than in endless abundance. This is practically part of the Japanese genetic makeup.

As for contemporary Japan, I was surprised to discover that Japan has more of what are called “complementary currency” programs—more than 600 of them—than any other country in the world. Some of these programs date from the seventies, and the number shot up dramatically as of 1995, when the effects of severe economic recession began to be permeate the country. Essentially, these are agreements within a community to accept something other than legal tender as a means of payment. They don’t replace the yen, as it turns out, they just run parallel to it as a kind of barter system, similar to what I described for Barcelona. Lifestyles among the youth have also begun to move in new directions, with a strong decline of interest in luxury goods. This is the so-called “satori generation,” the youth who prefer to keep things small, and who embrace sustainability rather than consumption. Many young adults have begun to explore careers in rural agriculture, for example, and the Japan Organization for Internal Migration runs a web site that assists them in resettling in rural communities and starting to live sustainably. These folks have rejected the rat race of Toyota and Mitsubishi in favor of “careers” in fishing, or making jam, and Japanese magazines occasionally run feature articles on how they are involved in organic food-growing, or crafts, or something outside the dominant capitalist framework.

[continues]

I did have a discussion with one young man who was himself not part of this movement, but told me that his parents’ generation was. He guessed that overall, the percentage of Japanese who have gone in this direction was small, but that there was nevertheless a large unofficial network of people who had turned their backs on mainstream consumer society. “They believe that capitalism is a dead end,” he told me, “and that as it continues to fail, alternative lifestyles will become increasingly attractive, as well as necessary”—a good summary of what I am calling Dual Process. Even at the official level, Japan has much to its credit, ecologically speaking. The domestic solar power market in Japan reached something like 20 billion US dollars in 2013; and the nation’s “ecological footprint,” defined as the per-person resource demand, is comparatively light. Whereas the United States placed fifth-highest on the list of the Global Footprint Network for 2007, Japan ranked thirty-sixth. There is some awareness, writes Azby Brown in his book, Just Enough: Lessons in Living Green from Traditional Japan, that “sustainable society will come because the alternative is no society at all.” Thus social critic James Howard Kunstler was led to make what he called “one flat-out prediction,” just a few years ago, namely that

“Japan will be the first society to consciously opt out of being an advanced industrial economy. They have no other apparent choice, really, having next-to-zero oil, gas, or coal reserves of their own, and having lost faith in nuclear power [not enough, unfortunately—they continue to remain schizophrenic about this, even after Fukushima]. They will be the first country to enter a world made by hand. They were very good at it before about 1850 and had a pre-industrial culture of high artistry and grace.”

Hi, Linh. I don't appreciate Berman, but he may be right about Japan. Thank you for the interview with Shibata, altho I think he is too easy on u.s.

I just wanted to let you know: Kensington was featured in Chris Hedges article about the Dems convention in Philly, which highlights the work of Cheri Honkala [EXCERPT]:

“Philadelphia has a poverty rate of 26 percent,” she said when I reached her by phone. “It has the highest number of people who die from drug overdoses in the country. The city has not housed anyone within the homeless population within 10 months. It has lost its state certification for the Department of Human Services child protection agency because of gross negligence and substandard conditions for children. Foster kids are stuck in an abusive system. Hundreds are not being placed. And at the same time, the city will spend $43 million on security for the convention. It will spend upwards of $60 million to house millionaires and billionaires while it ignores the vulnerable and attempts, by denying us a permit to march, to render them invisible.”

"She said that the difference between the march she led in 2000 and the one planned for July is that “things are four times worse.” She spoke about her north Philadelphia neighborhood, Kensington, the poorest district in the state. It has one of the highest homicide rates in the nation. It has a large homeless population. It has a poverty rate of 46.9 percent. The food bank is protected by barbed wire."

WHOLE ARTICLE HERE: http://www.truthdig.com/report/print/shut_down_the_democratic_national_convention_20160605

Makes me glad I have voted for those women in the past. But I think I'm over voting.

Anyway, wanted to pass this along.

Hi Linda,

This is my longest piece on Kensington, from 2013.

Linh

Thanks Linh. If Kunstler is correct. Well, pull saws, some farming, fishing sound good. An "American Satori generation" if possible - sounds like an end to the normal grind. Or rat race, or maybe drop dead race, or just plain goddamn misery.

Less ashamed of being lazy, as Shibata says. I'm sure that's popular everywhere, but the PTB aren't having any of it. "lazy" is more of an accusation, isn't it? That's what the boss wants us to do, go after the lazy people. To hell with that, let's help Patrick.

Maybe we should imitate Shibata, especially when we are mouthing off.

Hi jac.bane.sr,

The majority still don't think we're in deep trouble, and by we I also mean the entire world. The campaign rhetorics of our presidential candidates have become delirious. Renewed prosperity are just around the corner if only you'll elect me, each is promising.

Linh

Hi, Linh. Your Kensington article from 2013 is a tour-de-force carnival of humanity. It should be required reading for every one of those jerks running for office at any level in this circling the drain empire. Linda

Hi Linda,

If you and your husband ever show up in Philly, I'll take you to Jack's Famous Bar in Kensington. I've done that with a few out-of-town visitors already. That place has some serious character!

Though he had talked so eagerly and showed me his entire house, the weird landlord in my Kensington Postcard didn't recognize me the very next time he saw me.

“I’ve had people die in every single room of this house. See that chair there? A woman died sitting right on it!”

Linh

Post a Comment